Manga Review: Ayako by Osamu Tezuka

Osamu Tezuka is best known in the United States for his early children’s manga and their subsequent animated adaptations like “Astro Boy” and “Kimba the White Lion.” But later in his prolific career, he also produced quite a few works for more mature readers, such as “MW” and “Ode to Kirihito.” Ayako falls into the latter category.

The year is 1949, and the last of the Japanese POWs are returning to Japan. Among them is Jiro Tenge, second son of a wealthy landowning family. Times are tough for the Tenge clan due to the occupation’s land reforms breaking up their holdings. They’re desperately trying to hold on to their remaining prestige, a task made more difficult by the family’s dark secrets. Jiro has his own secrets from the time he was in American captivity, and soon there is death in the story.

Soon, it is decided that the only way to protect the Tenge clan is to seal away the youngest daughter, four-year-old Ayako, in a cellar. There she remains for over twenty years while the rest of the family sows the seeds of their own destruction….Given the recent cases of women escaping from long captivity, the story has a resonance today.

Even Tezuka’s children’s work did not shy away from deep themes (parental abandonment and racism in Astro Boy, questions of gender identity in Princess Knight), but this is a particularly dark work. In addition to the nudity and sexual situations you might have guessed from the cover, I need to issue TRIGGER WARNINGS for rape, child abuse, incest, torture, abuse of the developmentally disabled and domestic abuse. None of this is depicted as good things, but it can be seriously disturbing.

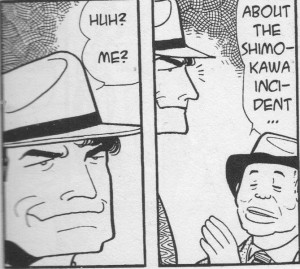

This story uses few of Tezuka’s trademark “stars”, instead trying to come up with new faces for its cast. One notable example is police officer Inspector Geta, who seems to be heavily inspired by Dick Tracy.

Bits of real Japanese post-war history are woven in, and there are footnotes indicating where this has happened. Tezuka’s explanation of events is not kind to the American Occupation.

Again, this is a book for mature readers. Late high school students might be able to handle it, but certainly not children. (Given the NSFW cover, you might not want to read it in public even if you’re an adult.) Recommended for Tezuka fans and those ready to explore the darker side of post-war Japan.