Book Review: The Boy Knight by G. A. Henty

G.A. Henty (1852-1902) was a writer of children’s historical fiction, who began his career as an author after a friend heard him telling bedtime stories to his kids. Like many Victorian authors, he’s out of favor these days, but my parents found this book at an estate sale.

Cuthbert is fifteen when the story begins, a lad of mixed Norman and Saxon blood during the reign of Richard I (Richard the Lionheart.) This gives him ties to both his late father’s cousin, the Earl of Evesham, and his mother’s relative, the landless freeman Cnut. Learning that the Earl plans to rid the forest of the landless men, Cuthbert warns them in time, then happily finds a way for the woodsmen to help save the Earl’s daughter from his real enemy, the Baron of Wortham.

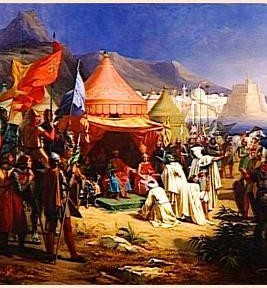

Recognized for his bravery and cleverness, Cuthbert is made the Earl’s squire when a Crusade is called. The noble (in the best sense of the word) lad is quickly noted by King Richard, and soon becomes a knight. Alas, after many adventures the old Earl dies without a male heir, but before he goes convinces Richard to appoint Cuthbert the new Earl of Evesham and the betrothed of the old Earl’s lovely daughter.

More adventures later, Cuthbert arrives back in England incognito, to discover that wicked Prince John has appointed one of his unpleasant cronies as Earl and betrothed. Now Cuthbert must defeat the false Earl, save the maiden and find the missing true king. With a little help from Robin Hood and Blondel, he accomplishes all this.

The prose is rather stiff with an antiquated vocabulary–today’s children might get the impression that they’re reading a book for grown-ups. Those looking for deep characterization are likely to be disappointed. Cuthbert begins the story honest, kind, brave and clever, and remains so throughout. His primary character flaw is that he is, perhaps, just a little too boyishly fond of adventure. When not engaged in battle, even the lowliest of persons is formal of speech.

This is not to say the work is free of moral ambiguity. It’s admitted that the Crusades had generally bad results in spite of their lofty purposes, the Muslims have valid reasons for opposing the Crusaders, and King Richard’s selfish actions are shown to have negative consequences even while he remains the great hero of the story. Parents reading this with their children may wish to discuss how easily religion can be used as an excuse for war, and the real history of the Crusades.

This book can also be found under the title “Winning His Spurs.” It’s a good example of children’s literature of a bygone age, and with some caveats is suitable as a bedtime story even today. As it’s in the public domain, there have been some inexpensive reprints in recent years.