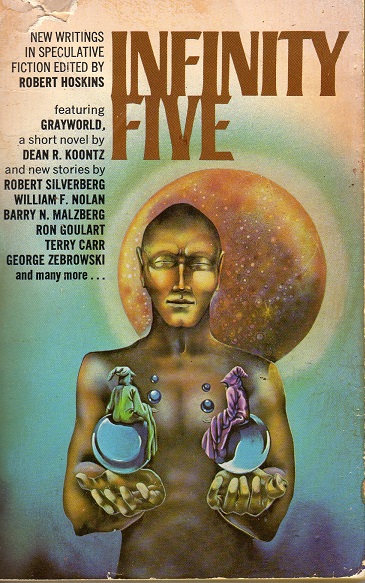

Book Review: Infinity Five edited by Robert Hoskins

This is the fifth and last (so far as I know) of the Infinity series of science fiction anthologies from Lancer Books. As mentioned in my review of Infinity Two, they’re heavy on the New Wave style of story, free to have sex scenes and rough language (but not yet skilled at their use) and experimental storytelling styles. The opening editorial mentions that SF has become a respectable genre for adults, but I’m not sure you could tell from this book.

SPOILER WARNING: I’m going to be giving away some of the endings.

“The Science Fiction Hall of Fame” by Robert Silverberg starts us off with one of the more experimental pieces, Short fragments from different stories cobbled together around the reminiscences of an avid science fiction fan who has a recurring nightmare about possible futures. It feels like Mr. Silverberg just grabbed random pages from rejected stories to fill out the length. At the end, the nightmare becomes reality, and the fear vanishes.

“In Between Then and Now” by Arthur Byron Cover is about two immortal and nigh-omnipotent beings that have been fighting since they can remember. One of them has a realization that his feelings have changed, but the other isn’t quite ready to accept this.

“Kelly, Frederic Michael: 1928-1987” by William F. Nolan is another “randomish fragments” story. Mr. Kelly is dying on an alien planet, and his mind slips back and forth.

“Nostalgia Tripping” by Alan Brennert has people listening to oldies radio, except that what precisely the oldies are, and the history that created them, keeps changing. It turns out that time travel has been invented and harnessed solely to change history to create these new “oldies” because 2003 is just that bleak. An interesting concept, but perhaps wasted on such a short story.

“She/Her” by Robert Thurston is about telepathic aliens whose planet is undergoing first contact with humans. Among the new concepts the visitors have brought with them is the significance of gender, as the humans innocently try to fit the aliens into their stereotypes. This is actually a decent story with a good try at thinking in alien mindsets.

“Trashing” by Barry N. Malzberg goes back to trippy as an assassin attempts to kill a madman who is spreading riots and disorder. Or is that really what’s happening?

“Hello, Walls and Fences” by Russell Bates is about an artist, or maybe an engineer, who’s asked to do something he finds repugnant by a wealthy man. Unfortunately, he’s got a wife to feed (this was back when most married women were expected not to have jobs) and his solo work doesn’t sell, so at the end he has to accept the rich man’s job. We never really find out what the process is or why the artist/engineer doesn’t like it.

“Free at Last” by Ron Goulart moves towards the silly. A man with a Wide Open Marriage in 1992 is cheating on it by having a secret affair with his invalid aunt’s nurse. Wide Open, of course, means no secrets. As part of this, he’s also concealing that his aunt is already dead. However, the man from the U.S. Department of Transition, which provides free funerals for all American citizens, is getting suspicious. This one has a lot of extrapolating Seventies California goofiness into the future. It’s maybe the best story in the issue.

“Changing of the Gods” by Terry Carr, on the other hand, takes a bitter approach to extrapolation. It is a future where all the mainstream religions have collapsed, to be replaced with the Ancient and Apostolic Church of Christ, Pragmatist. Yet they still have Fifties style ad agencies. Sam Luckman is a creative type for one of those agencies, which has been chosen by the Pragmatists to create an ad campaign for “family control” to battle the hideous overpopulation of the world. Luckman’s personal life is in the toilet, and his disgust with youth-oriented culture and the betrayal of his closest relatives boils over into the advertisements he creates.

Warnings for on-screen incest, pedophilia, castration, body horror. Also casual homophobia: “homosexual rapists” are said to haunt restrooms. This is all meant to shock, but just comes off as trying too hard. One begins to understand why Mr. Carr normally was restricted to editing.

“Interpose” by George Zebrowski has Jesus snatched from the Cross by cruel time travelers. Jesus is also an alien, not that it does him any good as apparently all his powers were withdrawn for the Crucifixion.

“Greyworld” by Dean R, Koontz is a full novella. An amnesiac man who is probably named Joel wakes up in a suspended animation pod in a deserted laboratory. After some wandering around, he runs into a faceless man and passes out. When Joel awakens, he’s still amnesiac, but is now in a New England country house with his hot wife and distrustful uncle-in-law. Several more layers of reality ensue. It’s similar in many ways to Keith Laumer’s Night of Delusions, which I reviewed earlier, but has a more stable (if highly implausible) ending.

“Isaac Under Pressure” by Scott Edelstein wraps up the volume with a quick joke story about unusual genie containers.

Overall, this collection has not aged well, and is only worth seeking out if you collect one of the authors whose story hasn’t been reprinted elsewhere.