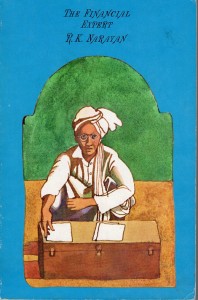

Book Review: The Financial Expert by R.K. Narayan

In the South Indian town of Malgudi, across from the Central Cooperative Land Mortgage Bank, there is a banyan tree under which sits Margayya, the financial expert. Margayya (“the one who shows the way”) is an unofficial middleman who helps the unlettered villagers apply for small loans from the bank (for a small fee), arranges for people who still have good credit to take loans to help out those with bad credit (for a small fee) and gives financial advice, among other services (for a small fee.) He works hard at his dubiously legal profession, from early in the morning to when the sun is setting.

The problem with nickel and diming poor people for a living is that at the end of the day what you have is a small pile of nickels and dimes. Margayya is on the “needs reading glasses” side of forty, lives in half a house with his wife and preschooler son Balu, and hasn’t bought a second set of clothing in years. When the Bank officially takes unfavorable notice of his business, and Balu playfully tosses the only copy of his financial ledger in the sewer, Margayya realizes that he needs a lot more money if he is to be treated with the respect he thinks he deserves. But where to get it?

R.K. Narayan (full name Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Narayanaswami, 1906-2001) is considered one of the most important writers of literature from India, at least partially because he wrote in English which made it easier to spread to the rest of the Commonwealth and eventually America. His novels and stories were set in the fictional community of Malgudi, a “typical” large town somewhere in southern India, which allowed him to invent geography as needed and avoid lawsuits when he used real-life incidents as the basis for the story.

In this case, Margayya is a composite of two real-life people, one an actual middleman who performed the services Margayya does at the beginning of the novel, and a high-flying financial wizard who was incredibly rich for a short time before crashing and landing in jail for his shady practices.

In the story, Margayya makes a fervent appeal to Lakshmi, goddess of Fortune, and in the process happens to run into a writer named Dr. Pal. Dr. Pal is interested in psychology, sociology and improving the life of his fellow humans. He’s written a manuscript that will eventually be titled Domestic Tranquility, an important sociological work to improve married life. To be blunt, it’s a sex manual. He gives the manuscript to Margayya to do with as he will, and the businessman gets it printed; the book is apparently phenomenally successful.

Mostly what Margayya does with his new-found cash flow is try to get a good education for his son Balu. Unfortunately, Balu is not the kind of kid that the formal education system of the time served well, and since no one ever bothers finding a better way to engage him, Balu becomes a wastrel instead. Part of the problem is that Balu has inherited his father’s habit of being sullen and silent when he has issues, and thus the two never have honest conversations instead of blowups.

Eventually, Margayya gets tired of the publishing business, where he never directly gets to see the money, and cashes out. With a substantial capital, he can now open a formal money-lending and investment business, becoming a “financial expert” who is respected by even the wealthiest men in town. But he again has left a single-point weakness in his business, which leads to ruin.

Margayya is not a very likable protagonist; he’s small-minded, sneaky and arrogant. He’s good at making money in the short term but poor at long-range planning. His relationship with his wife is more “she can’t bring herself to leave this jerk because there isn’t anything better for her in her society” than any form of mutual loyalty. Margayya’s constantly worried that other people are taking advantage of him, while taking advantage of others whenever possible. Margayya’s dignity is easily wounded, and he is quick to injure others’ dignity when he can. He loves his son, but completely fails to understand him, so the rottenness in the young man’s character grows.

The Time-Life edition, which is what I read, has two introductions, by the editor (you may want to save this one for after you read the book) and by the author. Mr. Narayan explains the background of the novel, including the economic conditions that lead to a cycle of debt, and how things had changed in India since the book was written.

There are several references to teachers striking students, and classism is often a subtext to what’s going on.

Recommended for those looking for a mostly realistic novel about life in India before independence with a not particularly sympathetic protagonist.

Hi Scott,

This looks like an interesting book. Why must we always like the protagonist? My husband and I just started watching House of Cards. Have you seen it? You have to love AND hate the main character, right from the first scene in the pilot. If you haven’t seen it, check out the pilot and let me know what you thought.

I’ve seen the British version many years ago. One of the things with “House of Cards” is that even though the protagonist is a horrible person, he’s also having fun being horrible. Margayya’s life is pretty much joyless, even when he’s raking in the dough as a predatory lender. He doesn’t even really enjoy his triumphs because he’s so convinced he’s going to be screwed somehow.

Which is not to say he’s not interesting, but sometimes I had to put the book down and watch something funny to cleanse my palate.

I’ve recently become curious about how the business of micro-loans developed and perhaps digging into this book will give me a different perspective.

This is more in the line of payday loans than micro-loans.

I hadn’t thought of Francis – the main character in House of Cards – but Amy’s right. I found myself conflicted with him – and that carried right through to the end of the current season. Great summation of the book, Scott. I grinned over the observation that he was on the “reading glasses side of 40.”

The reading glasses thing comes very early in the book, and shows some of Margayya’s character. He takes them on approval then just never returns to the shop and shames the shop owner into not trying to collect. Then he worries that people don’t respect him because he can only “afford” silver frames instead of gold, completely forgetting that he never paid in the first place.

This book sounds so intriguing to me! You totally captured my attention. By the way, the caste system in India is still such an important of their life. Great review…

When it comes time for Balu to be married, Margayya worries that prospective brides’ families will dig deep enough to learn some distant ancestors were corpse handlers.