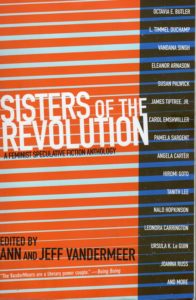

Book Review: Sisters of the Revolution: A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology edited by Ann & Jeff VanderMeer

As the subtitle of this volume indicates, it’s a collection of 29 short stories written from a feminist perspective. There are selections from the 1960s through the 2000s–SF, fantasy, horror and a couple of stories that seem to be included out of courtesy because of “surrealism.”

The anthology begins with “The Forbidden Words of Margaret A.” by L. Timmel Duchamp, an account of a journalist’s meeting with a woman whose use of language is considered so dangerous that a Constitutional amendment has been passed to specifically ban those words. The journalist has a photo-op with Margaret A. in the prison that woman is being held in, and the experience changes her. It’s an interesting use of literary techniques to suggest the power of Margaret A.’s words without ever directly quoting them.

The final story is “Home by the Sea” by Elisabeth Vonarburg, in which a gynoid in a post-apocalyptic world returns to her mother/creator to ask some questions. The answers to those questions both disturb and give new hope. Like several other stories in the volume, this one deals with the nature of motherhood, and the mother-daughter relationship.

There are some of the classic stories that are almost mandatory for the subject of feminist speculative fiction: “The Screwfly Solution” by James Tiptree, Jr. (men abruptly start murdering people they’re sexually attracted to, mostly women but the story tacitly acknowledges homosexuality); “When It Changed” by Joanna Russ (a planet with an all-female society is contacted by men from Earth after centuries of isolation–it originally ran in Again, Dangerous Visions, an anthology for stories with themes considered too controversial to be published elsewhere, times have changed); and Octavia K. Butler’s “The Evening the Morning and the Night” (a woman with a genetic disorder discovers that she has a gift that fits her exactly for a specific job, whether she wants that job or not.)

The anthologists have also made an effort to include stories that are “intersectional”, providing perspectives from other parts of the world. “The Palm Tree Bandit” by Nnedi Okorofor tells the story of a Nigerian woman who defies a sexist tradition and starts one of her own. Nalo Hopkinson’s “The Glass Bottle Trick” is a retelling of the Bluebeard story in modern Jamaica (this time the women avenge their own), and “Tales from the Breast” by Hiromi Goto, wherein a Japanese-Canadian woman discovers a solution to her breastfeeding problems.

Some other standouts include: “The Grammarian’s Five Daughters” by Eleanor Arnason (a fairy tale about language); “The Fall River Axe Murders” by Angela Carter (one of the stories that really doesn’t feel like speculative fiction, but is really well-written, set in the moments just before Lizzie Borden is about to get up and kill her parents) and “Stable Strategies for Middle Management” by Eileen Gunn (how far would you go to fit into the corporate culture? Would you let them shoot you up with insect genes?)

Tanith Lee’s “Northern Chess” is a fantasy tale of a warrior woman infiltrating a castle cursed to be a deathtrap by an evil alchemist. It’s exciting, but the ending relies on a now-hoary twist. Still worth reading if you haven’t had the chance before.

Most of the other stories are at least middling good. The weakest for me was “My Flannel Knickers” by Leonora Carrington, which falls into the surrealist category and seems to be about a woman who has rejected conventional beauty standards. Probably.

Rape, sexualized violence and domestic abuse are discussed; I’d put this book as suitable for bright senior high schoolers, though individual stories could be enjoyable by younger readers.

Recommended for feminists, those interested in feminist themes, and anthology fans.