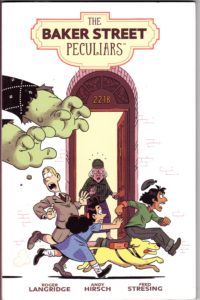

Book Review: The Baker Street Peculiars written by Roger Langridge, art by Andy Hirsch

It is 1933 in the city of London, and what appears to be a stone lion from Trafalgar Square is running wild in the streets. Three children from different walks of life (and a dog) have separately decided to chase down the lion to learn what’s going on. They eventually lose the trail, but meet the legendary detective Sherlock Holmes, who engages them for a shilling each to be his new Irregulars. They’ll investigate the supposed living statue while he’s busy with other cases.

But wait; assuming Sherlock Holmes wasn’t just made up by Arthur Conan Doyle, didn’t he retire to a bee farm in Sussex before World War One? There’s more than one odd thing going on here!

This volume collects the four issues of last year’s children’s comic book series of the same name. As a modern period piece, it’s a bit more diverse than the comic papers that would have been published back in the day.

Molly Rosenberg is a whip-smart girl, who wants to be a detective. Her kindly but conservative tailor grandfather has forbidden her formal education as he’s afraid she’s already too learned to attract a good husband.

Rajani Malakar is an orphan of Bengali descent who was raised (when not confined to juvenile institutions) by professional thief Big Jim Cunningham. Big Jim had an alcohol-related fatality a bit back, and she’s had to make her way alone with petty theft. Rajani is probably the oldest of the children, as she’s hit puberty.

Humphrey Fforbes-Davenport is the youngest son of a large upper-crust family. Evidently he was unplanned and unwanted, as he was shipped off to a harsh boarding school as soon as possible, with only a golden retriever named Wellington as a valet. (Wellington doesn’t talk, so his level of intelligence is difficult to gauge.) Over the course of the story, Humphrey learns to weaponize his class privilege (within his own class, of course, it’s never done him any good, so he didn’t even realize he had it.)

As it happens, Molly’s cultural background is especially useful in this case, as the villain is Chippy Kipper, the Pearly King of Brick Street, a self-willed golem. Chippy has the mind of a small-time protection racketeer, but has realized that the ability to bring statues to life gives him an army with which he could take over the city–maybe the world!

The kids are on their own through most of the adventure. The sole representative of the law enforcement establishment is PC Plank, who’s intellectually lazy, and would rather arrest known riffraff Rajani than investigate any other possible criminals. Sherlock Holmes is…elsewhere…much of the time, and Daily Mirror reporter Hetty Jones is well behind the children in her investigations.

The art is cartoony, with several Sherlockian in-jokes hidden in the background. This serves to soften somewhat the several off-screen deaths.

This volume should be suitable for middle-schoolers on up. Parents may want to be ready for discussions on period sexism and ethnic prejudice. (There’s also a subplot about dog farts.)

It appears that this may be the first in a series about the kids–I should mention that despite the Holmes connection, this and potential future volumes seem more about the “weird adventure” than mysteries.