Magazine Review: Famous Fantastic Mysteries March 1944 edited by Mary Gnaedinger

Famous Fantastic Mysteries ran from 1939 to 1953 as primarily a reprint magazine. It was originally published by the Munsey Company to feature the many speculative fiction stories they’d published over the years in their non-specialist magazines like Argosy, to cash in on the now thriving SF magazine market. They’d had many fine stories over the years, such as A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool, and had new art commissioned for the stories from excellent artists, especially Virgil Finlay.

At the end of 1942, Munsey sold the magazine to Popular Publications, which changed the reprint policy to only stories that had not appeared in magazines before. They also switched the magazine to a quarterly schedule for the duration of the war. So the March 1944 issue was still early in their new policy, and the letters column reflects this, with several readers still arguing “no magazine stories” was a bad idea.

Back before internet archives, interlibrary loan, or even “Best of the Year” collections, tracking down a particular half-remembered story was an exercise in frustration, so this reprint magazine was a godsend and sold well.

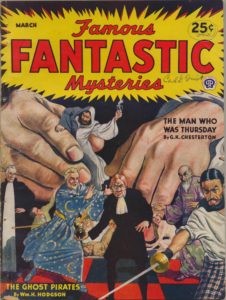

This issue has only two long stories (short novels), but they’re both indeed famous. Cover honors go to G.K. Chesterton’s “The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare.”

Syme is a philosophical policeman, part of a secret unit of Scotland Yard. As ordinary police officers deal with ordinary crime, a philosophical policeman deals with philosophical crimes that threaten to corrupt or destroy society. After a debate on what constitutes true poetry with a man named Gregory, Syme finds himself in a position to infiltrate the controlling council of Europe’s anarchist conspiracy. But has he bitten off more than he can chew, and who or what exactly is the remarkable Mr. Sunday?

As the subtitle suggests, the story runs on dream logic, and has many nightmarish qualities. The pursuer who moves slowly but cannot be escaped, the eyeless face, and the story’s biggest twist, which is famous but I won’t actually spoil in this review just in case.

Chesterton was a fervent Catholic, and his depiction of Anarchism as a philosophy may not be entirely accurate or fair. But it still leads to some hilarious moments in the person of Gregory, who tries to disguise himself as authority figures only to fail because he can only act out the negative stereotypes he has of them. And this moment, which commentators on the internet will surely identify with…

“I am afraid my fury and your insult are too shocking to be wiped out even with an apology,” said Gregory very calmly. “No duel could wipe it out. If I struck you dead I could not wipe it out. There is only one way by which that insult can be erased, and that way I choose. I am going, at the possible sacrifice of my life and honor, to prove to you that you were wrong in what you said.”

While the story starts out mostly plausible, the events become more and more unlikely, until the final scenes are almost hallucinatory. We finally learn most of the truth about Mr. Sunday, or at least what he wants us to know about him.

Some of the story’s digs at society may take knowledge of pre-World War One English culture to fully appreciate, but as an extended philosophical jest, it’s amazing.

“The Ghost Pirates” by William Hope Hodgson is about a sailor named Jessop, and the strange events aboard the ship Mortzestus. He hears even before shipping out on her whispers that the boat is ill-starred, but it’s going the direction he wants, and paying well.

At first, the rumors seem unfounded, but soon odd things are happening. There are too many shadows, some not cast by any living thing. Secured items become unsecured when no one is looking, and the sails behave as though there is wind, even when the air is calm.

When the ship is past the point of no return, the weird happenings turn dangerous, and then deadly. The ship has lost sight of its course, and there are shadows following it in the water….

Mr. Hodgson was a sailor himself for several years, and the story is soaked in authentic detail and nautical terminology. Having a dictionary handy for some of the obscure terms is recommended. For those who love sea tales and ghost tales, this is a well-told treat.

Both of these stories are in the public domain, and can be found free on the internet, or in your library.

The magazine also has a tribute to Abraham Merritt, who had long been a mainstay of its pages, and had recently passed away.