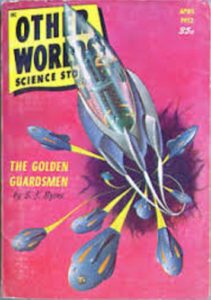

Magazine Review: Other Worlds April 1952 edited by Raymond A. Palmer

Other Worlds was a science fiction digest-sized magazine that began publication in 1949. Raymond A. Palmer was both the publisher and editor, and thus had a freer hand in choosing what to put in the magazine than most pulp editors. Mr. Palmer (whose name was borrowed for the secret identity of DC Comics’ second Atom as a tribute) had previously been the editor of Amazing Stories, where he had relied heavily on stories from the Shaver Mystery cycle.

In this issue’s editorial, Mr. Palmer discusses The Mature Mind by Harry Allen Overstreet, and flatters his readers (and to an extent all science fiction fans) that they are among the few who possess mature minds. Not blindly embracing the Shaver Mystery, or L. Ron Hubbard’s little philosophy experiment (you know the one), but not blindly rejecting them either.

I am of the mind that we should take this with a large grain of salt. Painful experience has taught me that I and other science fiction fans are also vulnerable to swallowing nonsense whole, especially when we flatter ourselves on being smarter than the average person.

The story content begins with “The Golden Guardsmen” by S.J. Byrne, part one of two. This turns out to be a sequel to Prometheus II. In that previous novel, reporter Stephan Germain battled the forces of Nicholas I, Emperor of the New Russian Empire. Stephan was captured and surgically altered into a powerful psychic in an attempt by Nicholas I to use the persuasive man to conquer the world. It didn’t work, as Nicholas’ allies, aliens we would call demons, were opposed by the ancient gods (more aliens.)

At the end of Prometheus II, Nicholas I and his henchman Pavlovich were spinning into empty space on an out of control ship, almost certainly dead.

We begin this story a few years later on the planet Mars. There’s a trade meeting of the nomadic free Martians at an oasis marked by a crystal pyramid. Among those in attendance is Trinha Llih, daughter of the greedy but lazy merchant Grlahn. Trinha has reached marriageable age, and is not displeasing to the eye. She knows that her father will sell her to the first man who offers a high enough price.

Like many young women in that situation, Trinha does not want to be auctioned off to some lout and spend the rest of her life in menial labor. She dreams of the fairy tale she heard as a child, in which a girl just like her turns out to be a princess in exile, and a handsome prince from Pahn (Earth) rescues her, taking her to his palace in the stars.

When two strange men stagger out of the desert, one quite handsome and possessed of both supermartian prowess and magical weaponry, Trinha sees her chance. True, her “prince” is rather older and more ragged than she had hoped, but he is a ruler from Pahn. Trinha is more than willing to help him against her superstitious people.

Unfortunately for Trinha, her “prince” turns out to be Nicholas I, who survived crashing on Mars. He’s here at the oasis to meet Izdran of the Thousand Lives, the being that more or less rules Mars. Emperor Nicholas, after securing Trinha’s vow to serve him, gives her to Pavlovitch, who is in need of some intimate healing if you know what I mean. (Nicholas himself is only interested in stealing Stephan Germain’s wife Lillian.)

Izdran is one of the few remaining survivors of the Nrlani, a species so powerful and evil that the Ancients had to blow up their entire planet (now known as the asteroid belt) to stop them. He’s been carefully building an army of telepathic robots and brainwashed Martians for millenia. Now that the ancient gods have finally left the solar system, Izdran is willing to ally with Nicholas I to conquer Earth, key world in controlling the area.

Naturally, Nicholas I and Izdran plan on betraying each other the moment it’s convenient. They’re both fully aware of this. What Nicholas hasn’t counted on is that Trinha now hates him with the fury of a thousand exploding suns, and plans to kill him the moment she sees an opening.

Meanwhile on Earth, Stephan Germain and his friends have turned control over the world back to the individual nations. But since the ancient gods left Germain in charge of protecting Earth, he would like the United Nations to give him the power to take over any time the Earth is in danger from outside forces. Forces that only he can detect.

Understandably, some of the various national governments are reluctant to give emergency powers to someone who could declare an emergency any time he felt like it. Even if some of them have ulterior motives, Stephan acknowledges that they have a point. He knows that he is completely trustworthy and that he and a handful of other enlightened souls are Earth’s last best hope, but he can’t demonstrate that without revealing a whole host of secrets the world is not yet ready for.

Germain’s forces detect that something is up (Izdran’s invisible war fleet) and Stephan sends his wife Lillian into hiding for her safety. This proves to be absolutely the wrong move, and now Stephan is dangerously vulnerable as the Nicholas I/Izdran alliance strikes!

There is some good world building in the early chapters, and Trinha is a sympathetic character. I felt for her when Trinha’s fairy tale prince turned out to be a louse.

Other characters don’t get nearly as much development–Nicholas and Izdran are sneeringly evil while Pavlovitch is a touch less ruthless, being more reluctant to dispose of possibly useful people. Germain and his bunch are generically heroic.

One bit that struck me odd was when the heroes cited falling church attendance as evidence that something evil is going on–when all gods and devils were revealed as just powerful aliens in the previous volume.

I can’t give a full rating to the story as this is only the first half.

If this story sounds like your cup of tea, I am happy to report that both Prometheus II and The Golden Guardsmen were reprinted a few years ago and you can probably find them on bookstore websites.

Next up is “Tradition” by J.T. McIntosh. Alan Gladwin was a mechanic out in the sticks, and doing all right for himself until a swindler took him for everything. Problem: The crook headed straight for Pluto, outside the extradition zone. Solution: stow away aboard the Space Navy ship Arachnid, blasting off for Pluto as part of a routine exercise. Perhaps Mr. Gladwin should have done some research first.

For when the stowaway is caught, it turns out to be Space Navy tradition to execute stowaways by firing squad. Oh, it seems that Mr. Gladwin has survived the firing squad? Because all the blasters were blanks? Then the next tradition is impressing the stowaway for a five year hitch in the Navy! And just in case he was thinking of jumping ship on Pluto, forget that.

The Arachnid isn’t going to Pluto. It’s headed to Venus to check up on the possible location of the Wreckers, a ruthless pirate gang. It had to be secret because the Wreckers have a inside man somewhere in the Space Navy command.

But despite the derailment of his initial plans, Spaceman Second-Class Gladwin is not just a survivor, but the sort of person who falls upward. As soon as he starts understanding how things are done, Gladwin rapidly finds himself Spaceman First-Class, and soon the most junior officer. It’s all down to tradition, you see. In the end, it’s Sub-Lieutenant Gladwin who figures out how the Wreckers are doing it and saves the day. By the end of his five year hitch, he might very well be Admiral Gladwin!

One tradition of the Space Navy I like is that men and women are treated as equals (at least theoretically), which gives a nice frisson to Gladwin’s relationship with Lieutenant Crisp. While she learns to appreciate his luck and/or skill, Lt. Crisp never has to be incompetent to allow Gladwin to shine.

I think fans of Irresponsible Captain Tylor would like this story.

Finishing out the fiction is “The Guardian of Eden” by Richard Ashby. Ham actor and playwright J. Marty Reed and his long-suffering troupe are engaged to put on an entertainment for the Servant of Tombola, a mining center asteroid. It isn’t going well until Marty drunkenly buys a device for creating plays that are exactly tailored to one person’s interests.

The Servant reluctantly agrees to have the device used, and the results are tabulated. There’s an issue, though. The Servant’s ideal female lead looks nothing like either of the actresses in the Reed troupe. Oh, there’s an advertisement for a free sample gynoid with overnight delivery! What luck!

The artificial woman Eden arrives, and is perfect. Now the play can begin! But it quickly becomes clear to the reader, if not Marty, that something suspicious is going on….

J. Marty Reed is a classic unreliable narrator, so caught up in himself and what he thinks is important that he misses vital clues and the real feelings of those around him. It got a bit uncomfortable for me after a while.

Then it’s off to the lively letters section (again, Mr. Palmer was his own publisher, so was only bound by postal regulations in what he could say in replies.) Two of the more interesting letters have to do with religion; one asking that OW not print stories disparaging Christianity, the other asking that it not print editorial material disparaging Mr. Hubbard’s philosophical experiment. Mr. Palmer defended his right to do both.

“The Man From Tomorrow” is an uncredited short-short, a utopian piece about simplified living. It has an end date of 1985, and well, that did not happen. “Fun With Science” is about imprecision in mathematical terms.

“Science Fiction Book Reviews” covers four classics of the genre: Farmer in the Sky, Seetee Shock, The Dreaming Jewels and The Voyage of the Space Beagle. It was a good month for science fiction!

And finally, there’s a biography of noted science fiction artist Hannes Bok.

That last one may make this issue a must-have for those with an interest in science fiction art.

A pretty solid issue altogether, though not a standout.

And since I mentioned Tylor, let’s see a bit of that show: