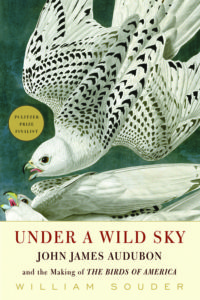

Book Review: Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of THE BIRDS OF AMERICA by William Souder

When John James Audubon arrived in Philadelphia in 1824, he carried with him a portfolio of beautiful bird paintings he hoped to turn into a book, and a backstory of childhood in Louisiana, being the son of a French admiral, and studying painting under one of the great artists of the previous era. The paintings were very well done, especially since Audubon insisted on always making them life-sized. But much of his supposed history was simply not true. In fact, John James Audubon wasn’t even his birth name!

Possibly worse, Audubon was seen as stepping on the legacy of Alexander Wilson, America’s greatest ornithologist to that point. Wilson’s life work, American Ornithology, had been posthumously completed by his friends, including one George Ord, a member of Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. Audubon reportedly was dismissive of Wilson’s accuracy and completeness, and claimed to have met the older man some years before, given him pointers, and then not given credit in the published version.

Ord was angered by this, and suspicious of Audubon’s wild tales of his past, blackballed the painter from Academy membership, as well as convincing the city’s publishers not to print Audubon’s work. Rejected, Audubon knew he would have to find another way.

That setback begins this biography of the famed painter and ornithologist. It then tracks back to his origins as they are now understood. The name change and fib about where he was born was meant to conceal that Audubon had been born out of wedlock in what is now Haiti. Some of the rest was to boost his social status, and the remainder was just the tall tales frontiersmen liked to tell.

This volume also serves as a biography for Alexander Wilson, and how the British immigrant weaver, poet and schoolteacher came to be one of the top experts on American birds. It’s interesting to compare and contrast his life to Audubon’s.

After things got dicey on Haiti for the French, Audubon’s father (who was merely a commander) took him to France to live with his family. When young Jean came of age, France was at war, and to avoid having the boy drafted, his father sent “John James” to America to manage some property there.

Audubon loved the great outdoors, especially the birds, and spent most of his time out there shooting birds and drawing pictures of them. He had his ups and downs, moving from place to place for business with mixed results, though his rambling ways seemed not to be the major reason for poor income. Indeed, he was doing quite well for a few years before the Panic of 1819 left Audubon and his family penniless.

Mrs. Audubon took on various jobs, mostly teaching, and their family resided with friends while Audubon buckled down to the project of creating as many bird illustrations as possible for the project he was sure would make their fortune. Once he felt ready, Audubon headed northeast to Philadelphia, with the results we have already seen.

Audubon scrimped and saved for a ticket to Britain, where he thought he might have better luck. As indeed he did. First in Scotland, then in England, Audubon’s bird paintings were a sensation. Alexander Wilson was a non-entity there, and Audubon’s outlandish ways and stories so denigrated in Pennsylvania were adored by the Brits.

The Birds of America found a printer there, as did the companion volume Ornithological Biography which not only described the birds depicted in Audubon’s pictures, but had sidebars on the author’s personal life. Alas, these sidebars are often at least partially fictional.

Audubon began having larger mood swings while residing in Britain, perhaps foreshadowing the mental illness he would have in his twilight years. (Constant exposure to arsenic, which was used to preserve bird specimens, probably didn’t help.) Eventually, The Birds of America was finished, though only a few hundred complete sets were ever published, and Audubon went on to other projects.

After John James Audubon died, his widow Lucy wrote a sanitized biography of him, which most children’s biographies of the man have worked from. Between that and his own habit of prevarication, it can be difficult to sort out what of his life is true.

The prose style of this biography is decent, and does not spend too much time on the drier side of history. I was a bit disappointed that there is only a small selection of black and white illustrations in the center, as the whole book is about the beautiful color paintings Audubon did. There are endnotes (good reading as the author sifts through the sources for reliability), a bibliography, and a small index.

Sensitive readers should be aware that there’s a lot of descriptions of hunting (Audubon was after all an avid hunter) and that Audubon, like many people who lived in Kentucky and points south during this time period, owned or rented slaves. (No quotes are cited about his personal feelings on the subject of slavery.)

This book would be best appreciated by bird lovers from senior high school level on up who want to know more about America’s early ornithologists.

While you’re here, if you like birds and want to support them, please consider donating to the Audubon Society, named after the fellow we’ve just been discussing. http://mn.audubon.org/support (Note: I am not a member of the Audubon Society and was not asked to provide this endorsement.)

And for those of you tired of the words, here’s some pictures: