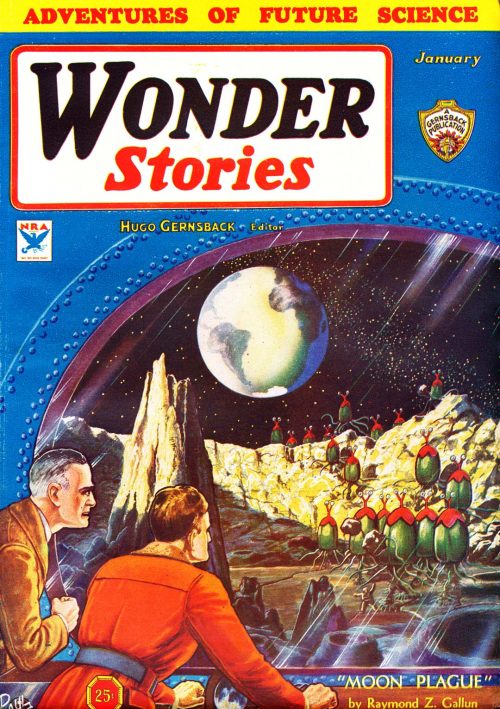

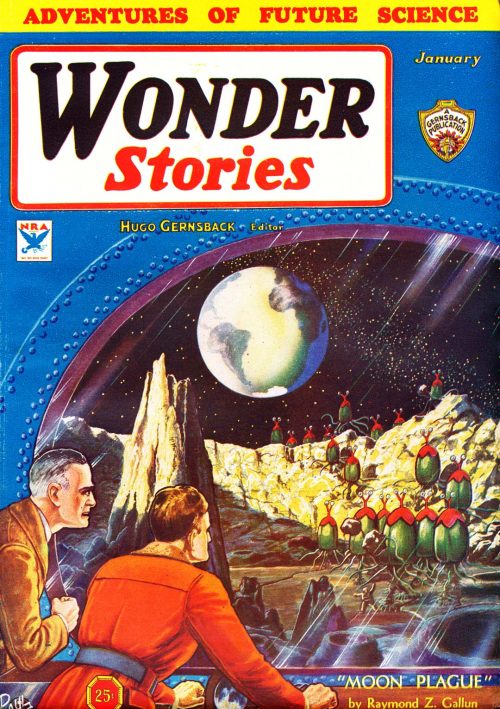

Magazine Review: Wonder Stories January 1934 editor-in-chief Hugo Gernsback

Wonder Stories was one of the first dedicated science fiction magazines, started up after Hugo Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories. It started in 1929 as two magazines titled Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories before being consolidated in 1930. He held onto it until 1936 when financial considerations made him sell it to Beacon Magazines. They changed the name to Thrilling Wonder Stories to match their other pulp titles, and this version was published until 1955.

As of the issue I’m reviewing today, the story editor was Charles D. Hornig, who favored fresh ideas that didn’t retread classic stories, and were somewhat plausible given scientific knowledge of the time. A laudable editorial philosophy, though 80+ years later, we might find these stories outdated and scientifically implausible.

The opening editorial is “Wonders of Micro-Life” by Hugo Gernsback. In specific, the many microbes that live inside the human body and help it to survive. The emphasis is on the vast amount we still didn’t know due to the limitations of microscopes at the time. (And we’re still learning!)

“The Exile of the Skies” by Richard Vaughan is part one of three. Knute Savary is a scientific genius who has very nearly conquered the Earth with televisors, death rays and weather control machines. He’s stopped in the final stages of the plan by forces of the World Council who somehow learned the location of his secret base.

However, the World Council is reluctant to destroy such a fine mind, and several of them like him personally. His contributions to the world of 2247 have been many. Too dangerous to remain in prison as he has fanatical followers, Savary is sentenced to exile. They’ve adapted his self-designed spacecraft to be unable to return to Earth or any Earth-like planet, loaded it up with supplies and lab equipment, and so Savary is shot into the skies.

Savary soon discovers there is a stowaway aboard the craft, Nadja Manners, herself a brilliant scientist. As it happens, she was the one female scientist Savary had ever employed, as she was the one woman who seemed emotionally stable enough to do the work. (Savary is kind of sexist.) She was the one who’d realized that Savary was the secret conqueror trying to take over the world and turned informer.

Manners had felt a bit guilty about the whole betrayal thing, even if Savary had needed stopping, and when she realized the exile plan, used the backdoors she’d built into the spacecraft blueprints to stow away. Savary accepts this, as he needed someone to talk to anyway, and she is just smart enough to understand his exposition.

Now we finally discover his motivation was to save the Earth. Savary had discovered that Earth was losing its atmosphere at an accelerated rate and would be uninhabitable in a century or two. But as a graduate of the Lex Luthor school of scientific arrogance, Savary had decided to not tell anyone and take over the world so he’d be able to command all its resources to fix the problem.

By this time, they’ve reached the asteroid belt, and land on a large chunk of rock. It turns out that the asteroids are not, as you might have assumed, pieces of an exploded planet, but miniature worlds of their own, some of which have developed intelligent life. The civilization that used to inhabit this asteroid put themselves in suspended animation when their atmosphere suffered the same fate Earth’s is going to. Savary decides that this is the ideal place to try out his world-saving plan. If it’s successful, he and Manners can revive the ancient civilization and plan some way to get word back to Earth. If not, it’s not like anyone is going to notice.

The scientists start the project and also interact with other aliens in the neighborhood, fighting a robot revolt and learning about telepathy. And this is just part one!

Knute Savary makes a pretty good antihero; you can see where his goals are good, but he’s not at all concerned with the human cost or collateral damage of his plans, and doesn’t even think until too late of maybe just explaining what he’s up to.

A paperback edition of this novel came out in 2016, but I am reluctant to read it, as there might be a romantic angle squeezed in at the last minute, and I like my headcanon that Savary and Manners are asexual/aromantic and just appreciate each other’s minds, which is fully supported in Part One.

“The Man from Ariel” by Donald A. Wollheim is the reason this particular issue was chosen for reprint, as it’s his first published story. Alas, he was not paid for it, and had to lead a writer’s revolt to get his back pay. Mr. Wollheim would go on to become the head of DAW Books.

The story itself is a sad tale of a space-traveler from Ariel, a moon of Uranus, whose spacecraft went off course and landed on Earth. It telepathically implants its story into the human that discovers it dying, then crumbles into dust. The main gimmick in the story is that due to Ariel’s light gravity, they are able to launch spacecraft with a Ferris wheel-like catapult.

It’s an okay short piece, but all idea and mood.

“To-Day’s Yesterday” by Rice Ray is set in Hollywood, where the wiring in a particularly ambitious tunnel set goes wonky in just the right way to allow filming and interacting with the distant past. The science idea here is that “time” is a wave function; you can travel through time, but only to times that are on the exact same position on the previous wave. The story is described as having “humor” but the ending kind of spoils the good mood.

“When Reptiles Ruled” by Duane N. Carroll barely counts as science fiction. It’s more a speculation about what dinosaur life might have been like during the Mesozoic Era. Lugi the Struthiomimus goes out looking for breakfast. Rayah the Pterodactyl objects to his raiding her nest, but Gundah the Tyrannosaurus is also hungry. Someone will be going home with a full belly. Very Nature Channel.

“The Secret of the Microcosm” by F. Golub is translated from the German, as Mr. Gernsback felt it was important to keep up with works from Europe. Professor Swenson has developed a new type of microscope with a projector screen that possesses unheard of magnification power. Soon our narrator is looking past the subatomic level to discover new worlds, but just as he’s about to see what an inhabitant looks like, the building catches on fire and all evidence is destroyed.

“Moon Plague” by Raymond Z. Gallum has the first lunar explorers encounter a biological infestation that first drives you mad and then slowly kills you. One of them manages to find a way of controlling the native life forms; unfortunately, he’s the one who was infected first. It makes for a nifty cover! As so often happens in early science fiction, one of the symptoms of the plague is that you monologue your entire backstory and master plan before killing the hero.

“Mr. Garfield’s Invention” by Leo Am Bruhl is also translated from the German. Mr. Jefferson is assigned to investigate what Mr. Garfield has invented, to see if it’s worth investing eighty million dollars in development. It’s actually two inventions. The first is a colorless, odorless, tasteless gelatinous soup that will deliver 100% of the daily nutritional needs for your average human being.

Garfield is aware that this stuff isn’t very appetizing, so the second half of the invention is a “taste ray” which sends “flavor particles” to the soup dish from a transmitter containing actual food. This is pretty nifty, though it’s not going to help with texture.

And it might well be worth investing in, but Garfield wants a signature on the dotted line now, and Jefferson is not authorized to do that. Garfield locks Jefferson in the testing room until he agrees, but Jefferson soon figures a way out. Unfortunately, all the evidence is destroyed. Again.

“Evolution Satellite” by J. Harvey Haggard is the final part of two. Bob and Gade have been sent to investigate the disappearance of several spacecraft near Uranus. They decide to investigate one of its satellites, only to have their ship eaten by one of the local plants. They escape and rescue a native girl from savages, but Bob is separated from the other two by another attack.

In this part, Bob tracks his companions across an ever-changing landscape, where all life “evolves” to better suit its surroundings. By the time Bob catches up to Gade and Nadia, they are nearly unrecognizable as they’ve “evolved” too and becoming mushroom-like fungus creatures that are best suited to the environment. Bob escapes the satellite, but is miserable back on Earth, because he also began changing, but while exposure to Earth conditions stopped the mutation it didn’t change him back. He ends his days as a night watchman to avoid contact with humans in the light.

“Impressions of the Planets – Venus” by Richard F. Searight is a melancholy poem about a Venus that never was. He did get the sulfur in the atmosphere right.

“Science in Fiction” is an editorial from the New York Times, no author listed, which talks about the difference between the fiction with science in of Verne and the science fiction of Wells.

“The Riddle” by Al Browne is a bit of doggerel about the origins of life. As you might guess, I am unimpressed.

“What Is Your Science Knowledge?” is a quiz to determine how much you retained of the science facts used in the stories this issue. Beware of your future knowledge tricking you into giving an unacceptable answer!

“Science Questions and Answers” has real-life science questions answered by actual scientists, about such topics as relativity and centrifugal force. Great stuff for the budding science buffs in the readership.

And finally, “The Reader Speaks” is the mail column. There’s discussion about whether science fiction pulp magazines need such gaudy covers (yes) and new fan clubs being formed, and there’s even a letter from superfan Forrest J. Ackerman!

Truth be told, all of the stories in this magazine are of the very old type of science fiction that takes some getting used to by modern readers. “When Reptiles Ruled” is probably the one that’s aged the least badly. On the other hand, “The Exiles of the Skies” has a lead character who’s unusual for his time and a lot of cool ideas stuffed into it.

The reprint publisher, Adventure House, does a nice job and uses a print on demand system so their offerings are almost always in stock.

Recommended for DAW completists, and SF fans looking back at the early stages of the field.