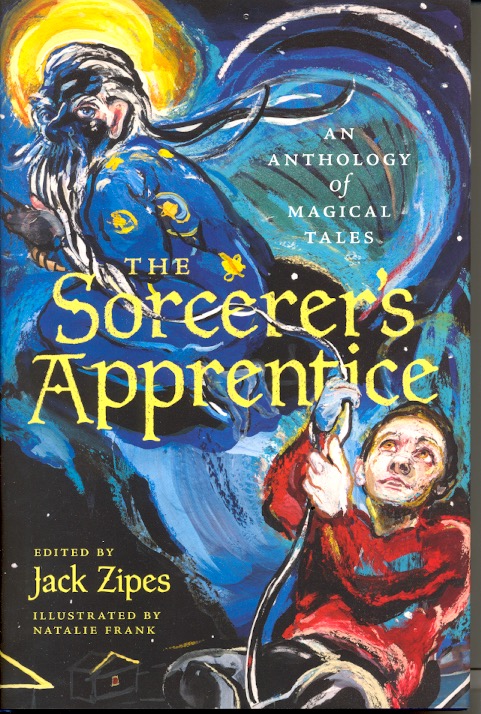

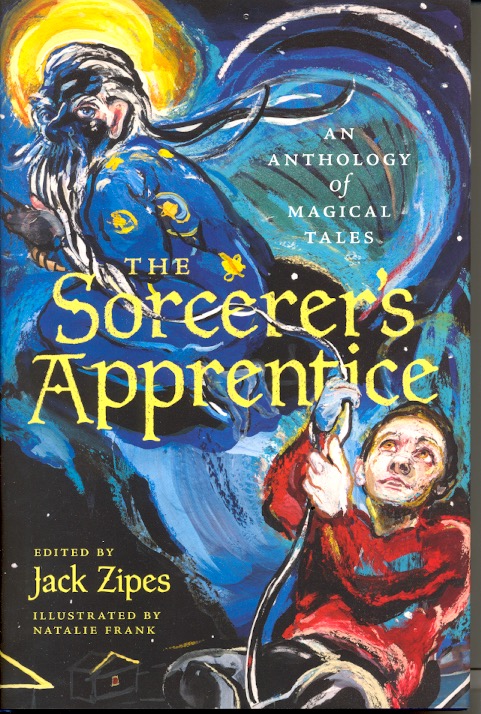

Book Review: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice edited by Jack Zipes

Most likely, when you saw this title, you immediately thought of the Fantasia sequence with Mickey Mouse, or perhaps the more recent Disney film with Nicolas Cage. But the multiplying of brooms is only one aspect of the tales gathered under the general title of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” As Princeton professor Jack Zipes explains in his lengthy introduction, there are two main categories: “The Humiliated Apprentice” who attempts a magical feat only to learn that he is in no wise ready to control it; and “The Rebellious Apprentice” who overcomes his master, usually in a contest of shapeshifting.

This anthology collects tales of these two types from around the world, both older variants and modern versions, plus a special section of Krabat tales. These last are a variant of the rebellious apprentice stories told by the oppressed Sorbs of Lusatia (and the fact that most of you have never heard of the Sorbs gives you an idea of just how oppressed), taking a possibly historical figure and turning him into a folk hero.

Professor Zipes’ introduction is quite lengthy, as this is a scholarly volume. It ranges on subjects from the Harry Potter series to the idea of the “memeplex.” It also talks about how these shapeshifting stories tend to be gendered; on the rare occasion that it’s a woman with such gifts, they’re used as a method of avoiding unwanted marriage and go away when she chooses to marry, whereas male protagonists use them to save their own lives and to get money.

The stories themselves are all short story length, or short stories extracted from within a larger work; longer pieces can be found in the bibliography. There’s a fascinating variety of sources, from the tale of “Eucrates and Pancrates” by Lucian of Samothrace, the earliest known written example of the humiliated apprentice version, through African-American folklore, Hindu texts, and literary fairy tales by such authors as E. Nesbit, to Jerzy Slizinski’s 1959 “Krabat” which sums up the tradition that had grown around the character.

Despite the many variations imposed by the cultures they were told in, the stories tend to be very similar in structure, and often have identical plot beats. (Being sold as an animal, turning into a ring to hide, needing a parent or lover to be able to tell which of a number of identical animals they are, etc.) This can make reading the book straight through a grind; it’s more of a scholarly text than an anthology meant for long reads.

That said, many of the individual tales are very enjoyable on their own, so dipping into this anthology from time to time when you’re in the mood for this sort of story will suit.

The illustrations by Natalie Frank are fantastical but often brutal-looking and can sometimes be difficult to puzzle out. The art emphasizes that this is not a book for children.

Content note: there is scattered racism and ethnic prejudice; evil sorcerers are often foreigners. People turned into animals are often abused.

The book concludes with minibios of the featured writers, a filmography and bibliography, a list of apprentice tales including ones not selected for this volume (and by no means still complete), and an index.

I’d recommend this volume primarily to literary scholars interested in fairy tales and related subjects; everyone else might want to check their local libraries for a copy to skim.

And here’s a trailer for a movie about Krabat!