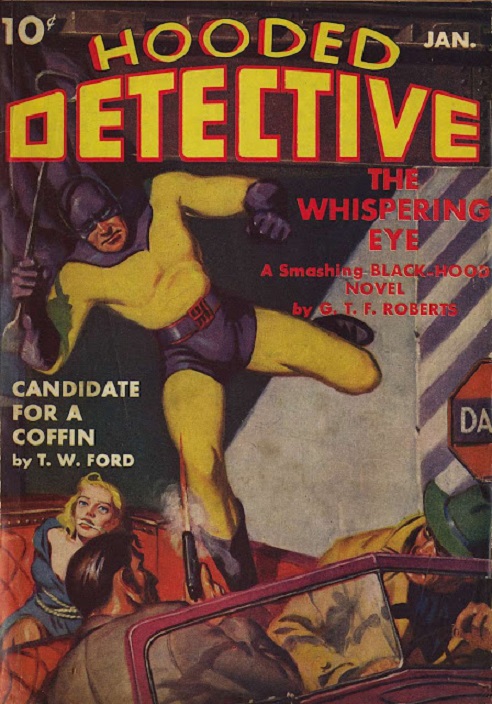

Magazine Review: Hooded Detective January 1942

The Black Hood was one of the superheroes created for the MLJ (later Archie) Comics line, first appearing in Top-Notch Comics #9 in 1940. Matthew Kipling “Kip” Burland was originally a rookie cop who was framed for grand larceny and injured to near death by a criminal known as “the Skull.” He was found and nursed back to health by a man referred to only as “the Hermit” who trained him to become a physical and mental marvel. Donning a yellow and black costume including the hood he was named after, the Black Hood cleared Kip’s name and defeated the Skull. Finding that the vigilante life suited him, Kip decided to continue wearing the mask.

Despite the relative simplicity of his design and modus operandi, or perhaps because of it, the Black Hood was one of the most popular MLJ characters in the early 1940s, and was spun off into a pulp magazine as well. It was titled Black Hood for the first few issues, then retooled as Hooded Detective for the last few, with the January 1942 issue being the last.

“The Whispering Eye” by G.T. Fleming-Roberts is the lead story, which naturally stars the Black Hood himself. A new criminal mastermind, the Eye, has taken over the various small gangs operating in New York City. Few have seen him, and when they do, he is always wearing a white rubber mask and delivering instructions in a whisper. Today’s job is stealing a large shipment of bonus money being delivered to a factory.

The Black Hood arrives just a little too late, and happens to be photographed in a position that makes it look like he was the one who murdered the gate guard. Since the police don’t trust the violent vigilante, this is all the evidence they need to declare that he’s the Eye. Even reporter Barbara Sutton, the Black Hood’s love interest (who doesn’t know he’s also her friend Kip) has to admit things look bad for the hero.

In a bit of a twist, the person the Black Hood was sure was the Eye turns up dead, but the Eye is still walking around and running his criminal operation just fine. He has to work out how this is possible. Amusingly, a clue the Eye originally meant to draw suspicion away is turned around to finger his true identity.

The Black Hood is your standard omnicompetent masked pulp hero, demonstrating whatever exotic skill he happens to need in the moment. He’s not excessively murderous, only shooting back at criminals with guns they were first trying to use on him. On the other hand, he conceals evidence from the police, and tortures a crook for information. (Yes, the crook in question had just tried to steam broil him, but I prefer my heroes not to use that as an excuse.)

Things are a bit more exciting on the villain side, as the various baddies are not exactly bound by honor among thieves.

“Candidate for a Coffin” by T.W. Ford stars Wilson Lamb, a young man hopped up on Nietzche and bad philosophy, who’s decided to murder a random person to demonstrate his ability to master reality (or some such nonsense.) He finds a likely person in the subway station and starts following him around to find just the right moment for his perfect crime. Lamb’s so far up his own hind end with his superiority complex that he fails to notice any of the clues that his target isn’t quite the sheeple Lamb thinks. Best story in the issue, spoiled a bit by the editorial blurb giving away the ending.

“One Hundred Bucks Per Stiff” by J. Lloyd Conrich has small town police chief Charlie Ward slightly surprised when a dead man walks into his office. It turns out that the corpse cooling in the basement is the man that stole this toxicologist’s wallet. The visitor is invited to identify the body, and it turns out that there’s a mystery the chief didn’t even realize was a mystery. The villain of the story turns out to be someone most people wouldn’t have suspected. This tale feels like it should have been the first in a series.

“Death Is Deaf” by Cliff Campbell is about a meticulously planned bank robbery that goes wrong when it turns out the head of the gang made one too many assumptions. This one has an unnecessarily violent ending.

“Three Guesses” by David Goodis has seedy private eye Frey and his assistant try to solve a murder by accusing the suspects one by one. Meant to be comedy, but falls a little flat. Content note: period racism by our protagonist and the narrator.

“The Cop Was a Coward” by Wilbur S. Peacock finds a seasoned police sergeant partnered with an eager rookie. Problem! Patrolman Burke has a yellow streak down his back. He draws his gun against a relatively harmless rowdy drunk, but not against a robbery gang that are firing at him, and abandons his partner. Sergeant Southern keeps quiet about the cowardice, but is about to ditch his unwanted partner at the first opportunity. Naturally, this is when Burke proves himself. Wastes the chance to talk about the police system and how it creates a culture of violence.

“The Strange Case of William Long” by Roy Giles is “true crime” about a Chicago gambler that disappeared in the two blocks between his hotel and an appointment with other gamblers. Most of the story is his history previous to this, and how he’d accidentally gotten rich from melon futures after starting a fruit stand as a front for a gambling den. The bit on the disappearance itself is disappointingly brief, as it’s just “we have no clues or suspects, and no one’s ever come forward with their story.”

“A Dinner Date with Murder” by Harry Stein is a short about two men waiting for an informant in a restaurant. All they know about him is his heavy accent, and there are two other men in the place, one of whom has the right accent, but doesn’t seem to be in any hurry to confirm that he’s the contact. The twist in the story relies on an outdated ethnic stereotype, but this use is somewhat clever.

“Artistic Murders Misfire” by Mat Rand is another “fact-based” article, discussing various virtually untraceable methods of murder available to the scientifically-trained. It’s both frustratingly vague because it doesn’t want to tell you the names of any of the chemicals involved, and annoyingly moralistic about how the murderers always get caught anyway, without going into any specific cases. Net information: zero.

This is a solid enough mystery pulp magazine. I read an Adventure House reprint but you may be able to find the text on the internet. Recommended to fans of any of the versions of the Black Hood that have been published over the years.