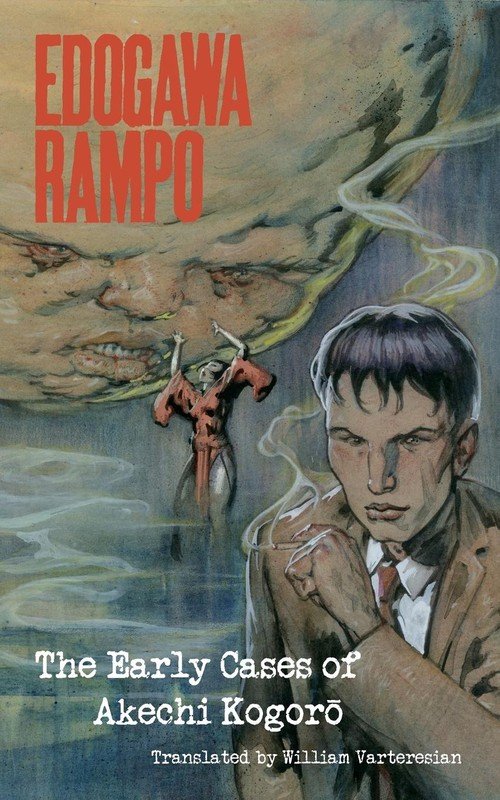

Book Review: The Early Cases of Akechi Kogoro by Edogawa Rampo

Edogawa Rampo was the pen name of Hirai Tarou (1894-1965), who I last talked about as the author of The Fiend with Twenty Faces. That children’s book featured Akechi Kogoro as the Detective Boys’ adult mentor, but he was already an established series character by that time. This volume reprints three of his early short story appearances, and his first novel length adventure.

“The Case of the Murder on D Hill” is the first Akechi story. Our unnamed narrator is between a young man between school and work, as apparently is Akechi himself. (Our narrator knows nothing of his background.) They’re both big fans of mystery and detective stories. One night they’re nursing cups at the coffeeshop on D Hill when they notice something odd about the used bookstore across the way. Although it’s open, neither the proprietor nor his wife has been visible for the last half hour. When they investigate, they discover that the bookstore owner’s wife has been strangled to death.

Various circumstances, including contradictory eyewitness evidence, make it seem to be an impossible crime. The narrator comes up with a theory with only one possible suspect–Akechi Kogoro! Fortunately, Akechi is able to explain where his friend went off the rails, and the true solution to the mystery.

This story was written to show that a “locked-room” type of mystery could be done in a Japanese dwelling, without the architectural requirements of Western houses. Initially, one of the clues was central to the solution, but feedback pointing out how unlikely it was caused Edogawa to have it be part of the false solution instead.

The story was written in 1925 but is indicated to have happened a few years before. At this point, Edogawa hadn’t fleshed out Akechi’s character, so he’s a bit of an enigma. He looks and has mannerisms like a local celebrity rakugo storyteller, dresses in a shabby striped kimono, and lives in a tiny room filled with books above a tobacconist’s shop. His interest in detection is entirely amateur.

“The Black Hand Gang” has the same narrator. While he’s down at heel himself, he has a rich uncle. That uncle’s daughter has gone missing, the work of the infamous Black Hand Gang. The uncle paid the ransom demand, but his daughter has not been returned as is the gang’s usual procedure. An air of mystery prevails because the gang member who picked up the money left no tracks! Akechi is called in and figures out how to find and rescue the young lady. Then he explains the twist to his friend.

Genre enthusiasts will easily figure out one of the twists. However, another one requires detailed knowledge of Japanese writing systems so will be opaque to most casual readers. Anti-Christian religious prejudice is a plot point.

“The Ghost” is the tale of businessman Mr. Hirata, whose rival Tsujido has finally died. Tsujido had vowed vengeance years before for reasons never actually revealed in story, so Hirata had been living in fear. But just as Hirata starts to relax, he gets a letter from Tsujido promising that Tsujido will become a ghost and haunt him from beyond the grave. Sure enough, Tsujido’s face keeps popping up in crowds and floating in photographs. Maybe he’s not dead? But the official records say he is! And Tsujido’s own son is acting as though his father is dead.

Near a nervous breakdown, Hirata goes on vacation to a spa, but even here he sees Tsujido! Also at the spa is Akechi Kogoro, who convinces Hirata to tell him the story, and figures out the truth of what has happened.

Most of the story is the mounting evidence of the haunting and Hirata sliding towards madness, with Akechi just showing up towards the end to resolve the matter.

“The Dwarf” was written in 1927, and marks the first of a series of changes in Akechi Kogoro. He’s spent a considerable amount of time in Shanghai and now habitually wears Chinese clothing, has a much larger room, and even subordinates as he’s now a professional private detective.

The protagonist of the novel is Kobayashi Monzo, who’s a lot like the anonymous narrator of the first Akechi stories. He’s between school and work, and knew Akechi back when they shared a boarding house. Late one night, bored but not sleepy, he goes to a city park to observe the night life. He observes a little person (the “dwarf” of the title) who is carrying what appears to be a human hand. He stalks the little person through the parks and the dark streets of Tokyo, losing sight of him when the pursued, apparently not aware he’s being followed, goes in at the gate of a temple.

When he goes to the temple the next day, Kobayashi is assured by the head priest that no such person entered the temple last night, or is even known there. Other people in the neighborhood confirm that they’ve never seen a little person at the temple or hanging out in the neighborhood, something they’d surely remember. Confused, Kobayashi is startled to be hailed by someone he knows, the lovely Mrs. Yamano. It turns out she remembers him mentioning his friendship with Akechi Kogoro and wants an introduction.

Mrs. Yamano wants to hire Akechi to investigate the disappearance of her stepdaughter Michiko. Michiko vanished from a locked house with no one seeing or hearing her leave, there’s no note or odd behavior that would indicate she left voluntarily, and no outside contact has found her elsewhere.

Akechi finds a previously overlooked clue that indicates Michiko has met with foul play. The hunt is on!

It turns out the family has several dark secrets, and a certain master criminal is taking advantage of this for his own agenda. Evidence seems to be piling up against Akechi’s client, Mrs. Yamano, but Kobayashi, who has the hots for her, is willing to step out of line to assist her.

This novel has some disturbing imagery, what with the severed limbs, deformity and repeated use of dolls going on. Large portions of Tokyo were poorly lit during the Taisho Era, so darkness closes in and conceals, with flashes of light suddenly revealing unsettling sights. A certain amount of this is misdirection, keeping the reader from figuring out too much before Akechi explains all at the end.

Some of the translation comes across as a little clumsy, or perhaps those bits were just odd in the original.

The ending is mostly satisfying, with Akechi showing his preference for merciful justice over a strict accounting to the law.

Content note: Ableism. The outdated word “dwarf” is used for a little person, and the narration also repeatedly calls him a “cripple” and “deformed child”. Prejudice against people with deformities is part of his background, and he’s not exactly treated well in the present day. There’s a bit of slut-shaming, and one of the characters is being coerced for what would be unwanted sex. In the initial chapter, Kobayashi witnesses what is implied to be a gay pick-up in the park.

Overall: A good selection of stories that gives an idea of Edogawa Rampo’s early style and puzzle building expertise. Recommended to mystery fans looking for something both old-fashioned and offbeat.

Do they ever state that Kobayashi is NOT the narrator of those first two stories?

No, there is nothing that directly contradicts this. On the other hand, you’d expect some references to those earlier cases if he’s the same person. Especially with the initial surface similarities to The Black Hand Gang case. There’s also nothing that says this Kobayashi isn’t the relative of Kobayashi Yoshio, who is Akechi’s assistant in the Detective Boys series. (The timing isn’t good for him being Monzo’s son.)